“For decades, scholars have quietly debated a startling possibility: the God of the Bible might have once had a wife. This revelation is rarely spoken of in churches, but it could reshape everything we thought we knew about ancient faith”

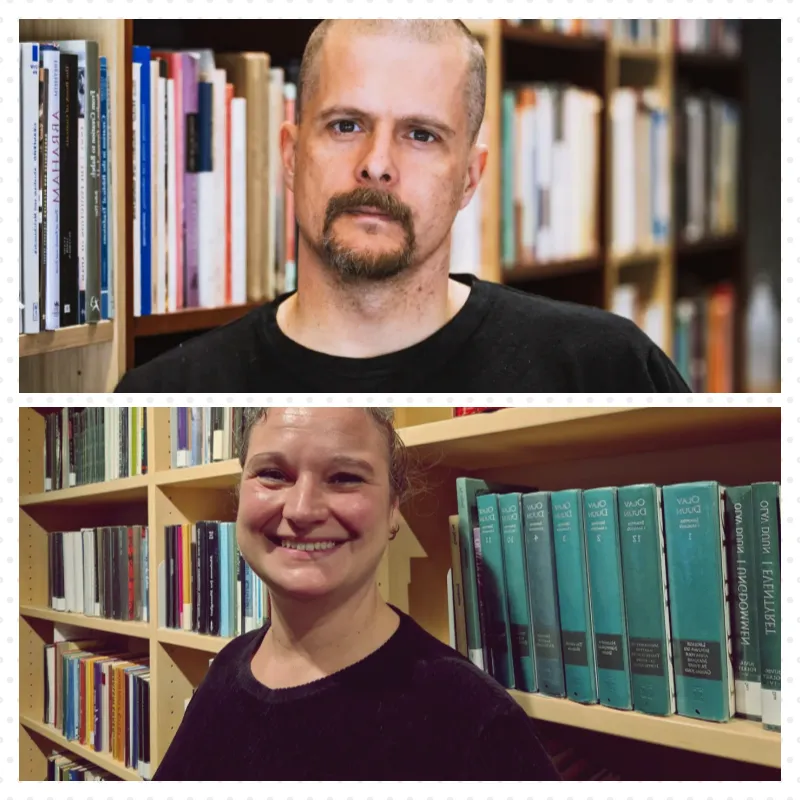

For over 30 years, a controversial question has quietly simmered among Bible scholars: Did God once have a wife? This idea, though rarely mentioned in sermons, could radically alter our understanding of biblical history. “We who study the Old Testament know that God has a past. The religion described in these texts didn’t just appear out of nowhere,” says Anne Katrine de Hemmer Gudme, a professor at the University of Oslo’s Faculty of Theology.

The story begins in a turbulent region of the Middle East, nearly 3,000 years ago. In this land of shifting sands and vulnerable kingdoms, the seeds of the Old Testament were sown amidst war and exile. Two small kingdoms, Israel and Judah, located where Israel and Palestine stand today, faced constant threats from more powerful empires. When they fell, their people were left to grapple with their faith and the gods they once worshiped.

Among these gods was Yahweh, who we now know as God. But Yahweh was not alone. In those days, he was one of many gods worshiped in the temples. When the temples were lost, the people turned to sacred texts as a guide, and over time, Yahweh rose to prominence. But what happened to the other gods, especially Asherah, who some believe was Yahweh’s wife?

Asherah’s presence is barely acknowledged in the Bible, but her traces are undeniable. Inscriptions from that era, found in places like Sinai and Jerusalem, depict Asherah standing alongside Yahweh. These findings suggest a divine partnership that the authors of the Old Testament sought to erase. “The way Asherah is treated in the scriptures is deeply fascinating. She is vilified and demeaned, yet evidence shows she was likely once Yahweh’s consort,” Gudme explains.

The writers of the Old Testament embarked on a fierce campaign to eliminate Asherah from the religious narrative. They equated her with false gods, urging the destruction of her symbols. “Tear down their altars, smash their sacred pillars, cut down their Asherah poles, and burn their idols in the fire,” commands Deuteronomy 7:5. This relentless propaganda gradually erased Asherah from the collective memory.

But the people resisted. As they faced war and famine, they lamented the loss of their goddess: “Ever since we stopped burning incense to the Queen of Heaven, we have had nothing and have been perishing by sword and famine” (Jeremiah 44:18). Yet, over time, the narrative shifted. The Old Testament writers emphasized Yahweh’s supremacy, and the idea of a single god took root.

Yahweh’s rise was not just a matter of faith but also of power and influence. The elites who penned these texts had the means to propagate their message, effectively creating a “divine advertising agency” for Yahweh. “It was not a given that Yahweh would survive the other gods, but sometimes coincidences and a bit of luck lead to events that change the world,” Gudme reflects.

Today, the idea that God once had a wife remains largely confined to academic circles. It challenges long-held beliefs and sparks intense debate, even among theology students. But as scholars like Gudme continue to explore these ancient texts, they reveal a complex and evolving portrait of the divine—one that may have included a forgotten goddess.