“Delve into the captivating legacy of Simonetta Vespucci, the muse behind Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus, and uncover the intriguing discoveries of Europe’s first oil adventure in Svalbard”

Simonetta Vespucci and Botticelli’s Divine Inspiration

In the labyrinthine corridors of Renaissance art, few figures cast a shadow as alluring as Simonetta Vespucci. Immortalized by Sandro Botticelli in his iconic painting, The Birth of Venus, Vespucci’s story is a tantalizing blend of beauty, art, and tragedy. The painting, portraying the Roman goddess of love emerging from a shell, transcends mere sensuality to embody a divine narrative of purity and rebirth. Yet, behind this celestial visage lies a beguiling tale of mortal enchantment.

Simonetta Vespucci, whose origins are debated between Genoa and Porto Venere, became an overnight sensation upon her arrival in Florence around 1469 at the tender age of 16. Married to Marco Vespucci, a cousin of the renowned explorer Amerigo Vespucci, Simonetta quickly captured the imagination of Florence’s artistic elite. Her unparalleled beauty made her the muse for several illustrious figures, including Botticelli.

Botticelli’s infatuation with Simonetta was profound. She posed for him as the goddess Venus, ensuring her image would be eternally linked with divine beauty. Intriguingly, Botticelli completed The Birth of Venus a decade after Simonetta’s untimely death at 22, during a period when Florence was engulfed in mourning for her. Botticelli’s devotion was so intense that he requested to be buried next to her, a wish fulfilled in their shared resting place at the Church of Ognissanti.

Not all historians agree that Simonetta was Botticelli’s muse, with some arguing that the connection is more romanticized than factual. However, the resemblance between Vespucci’s known portraits and Botticelli’s Venus, coupled with Botticelli’s personal connection, adds a layer of compelling intrigue to her legacy.

Investigating Graves from Europe’s First Oil Adventure

The story of Simonetta Vespucci’s ethereal beauty is matched by a different kind of discovery on the icy shores of Svalbard. Here, archaeologists like Lise Loktu are unearthing the remnants of Europe’s first oil adventure, an exploration driven by the insatiable demand for whale oil in the 1600s and 1700s.

Svalbard, a remote archipelago, became a hub of whaling activity, attracting adventurers seeking fortune in the oil-rich blubber of whales. The oil was essential for lighting, fabric preparation, and dyeing, while whale bones found new life as parasol ribs and corset stays. Despite the wealth generated, the whaling industry was perilous, leading to large grave sites with unique burial traditions for those who perished.

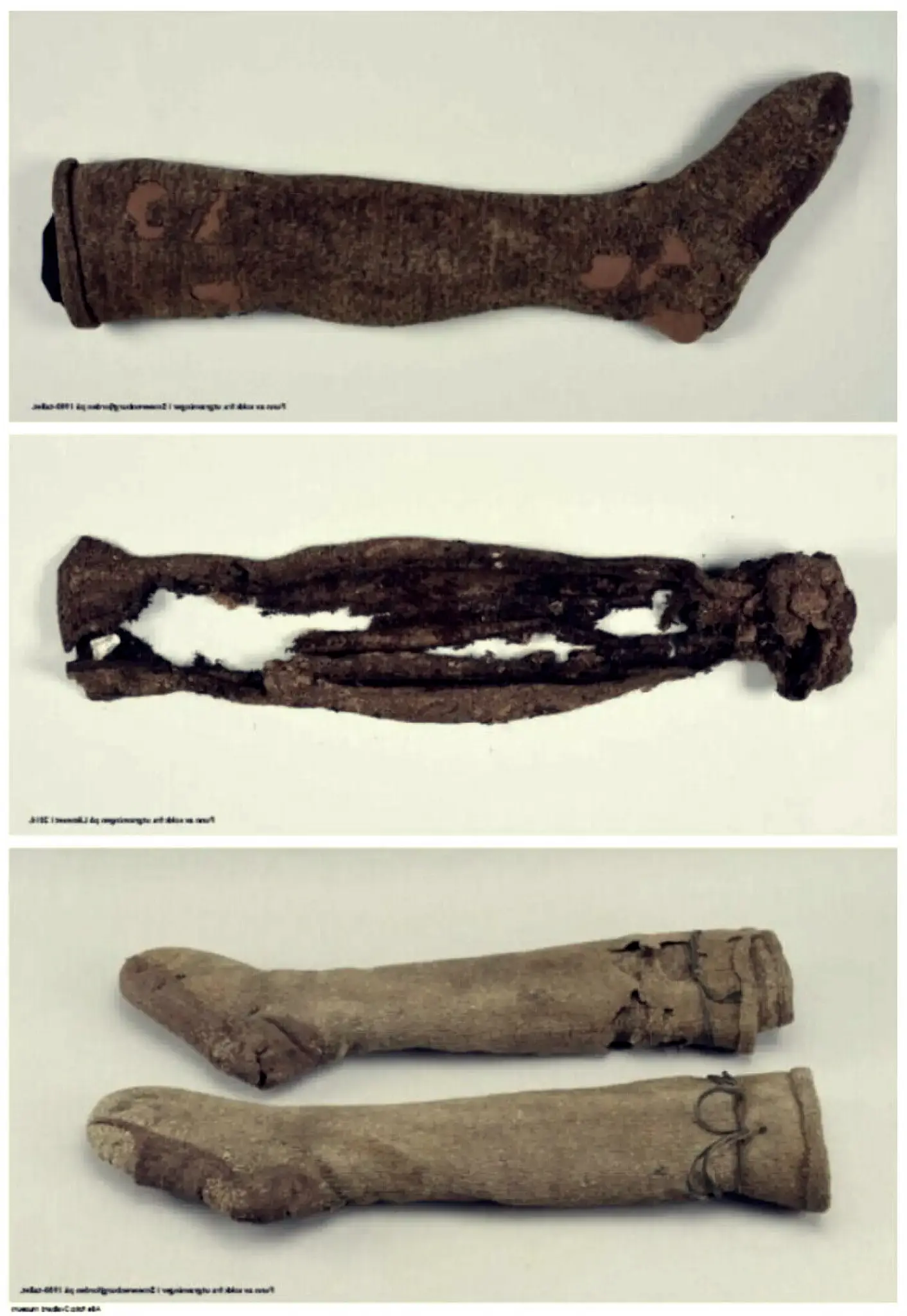

Loktu describes her work as “the absolute coolest thing” in her archaeological career. Among the 800 whaler graves found on Svalbard, the exceptionally well-preserved remains offer a glimpse into the lives and health conditions of these early adventurers. The frigid climate and permafrost have preserved not just skeletons but also remnants of hair, skin, and clothing, revealing the daily struggles and societal stratifications of the whalers.

The graves provide invaluable insights into the clothing and equipment of ordinary people, contrasting with the luxurious textiles typically displayed in European museums. The well-preserved artifacts suggest that whalers wore regular winter clothing from their homelands rather than specialized gear.

As erosion threatens to wash these graves into the sea, the urgency to preserve this knowledge grows. DNA and isotope analyses are shedding light on the whalers’ origins, diets, and genetic backgrounds, offering a broader understanding of their lives and the diverse nations they hailed from.

Loktu’s ongoing research aims to preserve and share these findings, bridging the gap between past and present. The discoveries in Svalbard, alongside the eternal allure of Simonetta Vespucci, remind us of the enduring connection between history and art, revealing the intricate tapestry of human experience across centuries.