The Mystery of the Missing Pregnant Porbeagle Shark: A Larger Shark’s Deadly Hunt

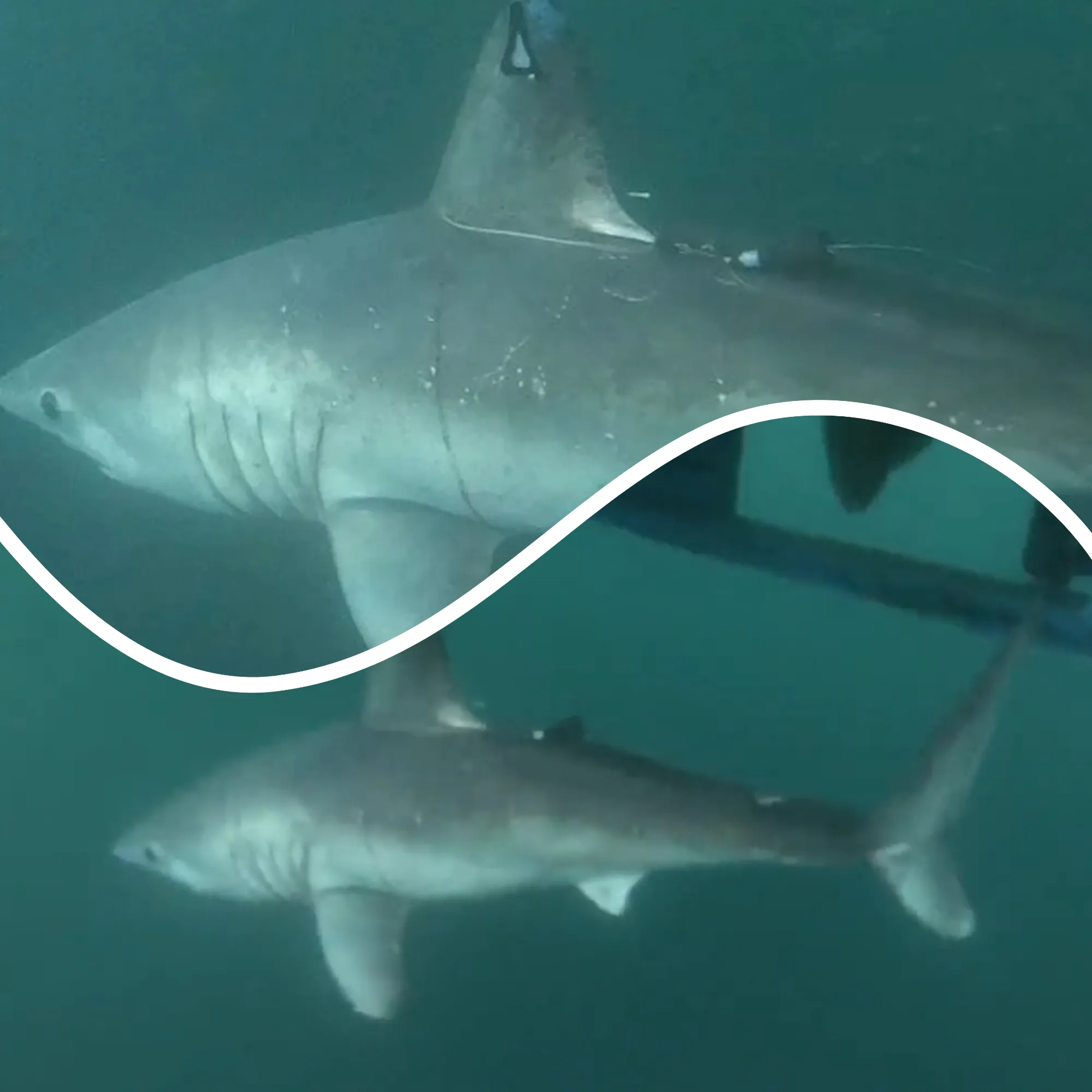

In October 2020, scientists embarked on an intriguing study by tagging a pregnant porbeagle shark to better understand its habitat. However, the research took an unexpected turn five months later when the shark disappeared, only to reveal a surprising discovery—another, larger shark had devoured it.

The First Documented Case of Shark-on-Shark Predation

This groundbreaking event marked the first-ever recorded instance of a porbeagle shark being preyed upon by another shark. According to Dr. Brooke Anderson, a marine fisheries biologist from the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality, this unique incident sheds new light on predator interactions among large sharks. Porbeagles, which inhabit the Atlantic, South Pacific, and Mediterranean, are elusive creatures. They can grow up to 12 feet long, live for 30 to 65 years, and reproduce only after reaching the age of 13.

Threats Facing Porbeagle Sharks

Porbeagle sharks are listed as vulnerable on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, largely due to habitat loss, overfishing, and bycatch. The loss of a reproductive female, along with her unborn pups, is a significant blow to the already struggling population. If shark predation on porbeagles is more common than previously believed, it could have devastating effects on their recovery.

The Hunt for Suspects: Great White or Shortfin Mako?

Following the disappearance of the tagged porbeagle, scientists narrowed down two prime suspects: the great white shark and the shortfin mako. Both are part of the lamnid shark family, known for their ability to regulate body temperature. Given the behavioral data from the tracking tag, Anderson’s team believes a great white shark is the most likely predator, ruling out the shortfin mako due to its distinct diving patterns, which did not match the data.

Technological Advancements in Shark Research

Researchers used satellite tags to track the porbeagle, which recorded its movements at various depths and temperatures. However, the sudden spike in temperature registered by the tag in March 2021 indicated that it had been swallowed by a warm-bodied predator, most likely a great white shark.

This discovery has broader implications for understanding predator-prey dynamics in the ocean. “We often think of large sharks as apex predators, but it’s becoming clear that their interactions are more complex than previously thought,” said Anderson. This new insight calls for further studies on how frequently large sharks hunt each other and the potential impact on marine ecosystems.

The Future of Shark Research and Conservation

Satellite tagging has become a vital tool for tracking sharks and studying their behavior, particularly for vulnerable species like the porbeagle. While the northwest Atlantic porbeagle population is stabilizing due to conservation efforts, continued protection is essential to ensure their long-term survival. As scientists continue to tag more sharks, they hope to uncover additional behaviors and interactions, contributing to the broader understanding of oceanic predator ecosystems.

In the case of the missing porbeagle shark, the scientific community has learned more than anticipated—highlighting both the fragility of this species and the complexities of marine life at the top of the food chain.