Exploring the First Viral Images: How Renaissance Art Captured Popularity and Spread Like Social Media Today

During the Renaissance, going viral took on a whole new meaning, particularly in Northern Belgium, a region that witnessed a remarkable socioeconomic boom from the 15th to the 18th centuries. This period saw the rise of a burgeoning upper-middle class eager to acquire status symbols. Art became a central means of achieving this, with the commissioning of paintings and the widespread distribution of imagery through new mass-printing technologies.

As cities like Antwerp, Bruges, and Ghent evolved into cosmopolitan centers of capitalist and colonial prosperity—fueled in part by their roles in the Spanish and Portuguese empires’ slave trades—art became a symbol of desire and social status. According to Chloé M. Pelletier, curator of the “Saints, Sinners, Lovers and Fools: Three Hundred Years of Flemish Masterworks” exhibition at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, displaying art was akin to flaunting wealth today. The exhibition, which runs until October 20, features 137 artworks from the period, showcasing pieces by renowned painters like Pieter Bruegel, Peter Paul Rubens, and Jacob Jordaens.

Much like the curated images shared on social media today, collecting art was a way to draw attention to one’s wealth. Consider a mid-17th-century painting by Michaelina Wautier depicting a man in a luxurious silk shirt posing with a Rubens painting. Such portraits were the Renaissance equivalent of an Instagram post, demonstrating the sitter’s prosperity and taste.

This new class of collectors paved the way for the modern art market. Artists, once tied to religious and aristocratic patrons, began to create works independently, selling them through newly established art dealers. This freedom allowed artists to depict both divine and everyday scenes, from Hans Memling’s luminous nativity scenes to Bruegel’s illustrations of domestic squabbles. Popular subjects often inspired multiple versions, capturing moments from bar brawls to depictions of the infant Jesus.

The rise of the printing press further accelerated the spread of these images, making them accessible not just to collectors but to the general public, effectively making them “viral.” Stephanie Porras, an art historian and author of “The First Viral Images: Maerten de Vos, Antwerp Print, and the Early Modern Globe,” explains that the concept of virality helps explore how images circulated through gatekeepers and social networks of the time.

Collecting art became a social activity. With households averaging about 30 paintings, identifying a painting’s creator became a party game. These artworks served as conversation starters, much like contemporary pop culture references.

The art world of the Renaissance was also an early platform for self-branding. Paintings like “Elegant Couple in an Art Cabinet,” by Peeter Neeffs the Younger and Gillis van Tillborch, capture individuals surrounded by their art collections, showcasing their wealth and sophistication. However, while art displayed luxury, it also conveyed piety through religious motifs, reminding viewers of mortality and humility.

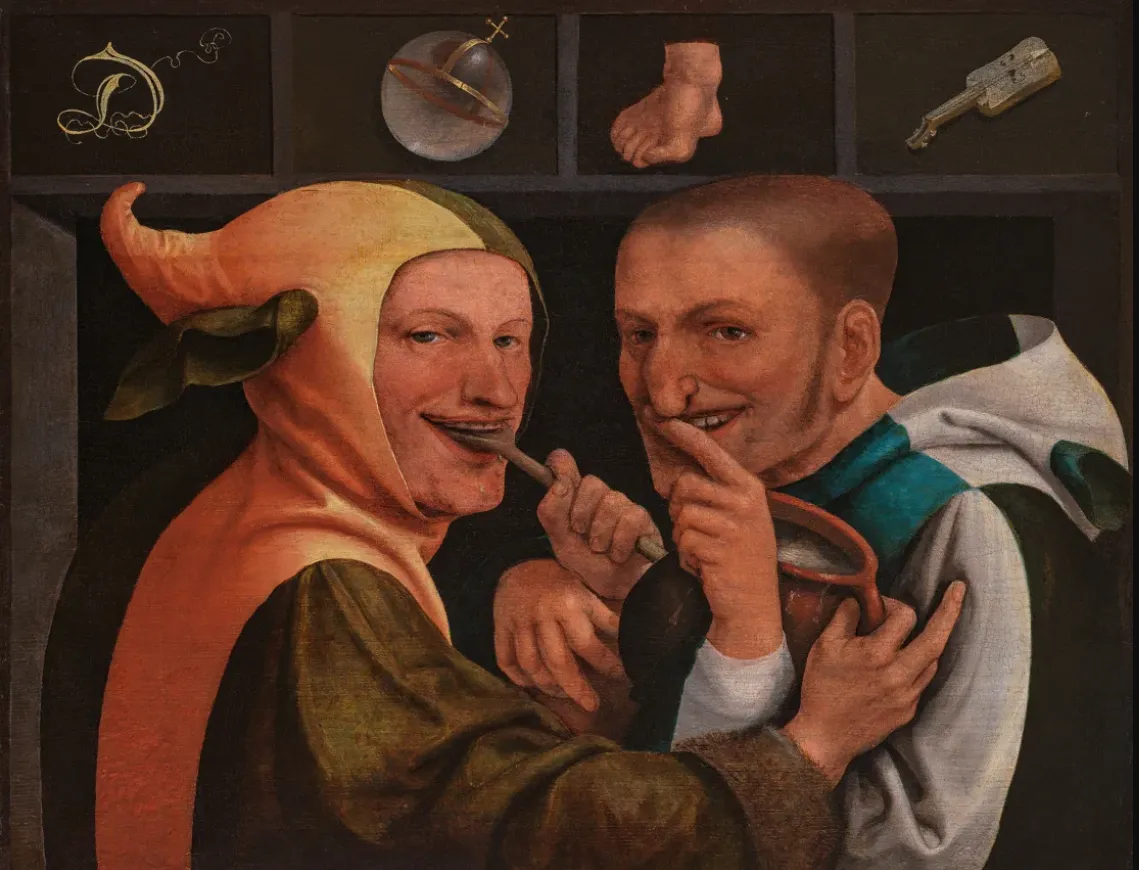

Viral imagery occasionally provoked reactions, from satirical pamphlets to public commentary, much like today’s social media backlash. Art was a form of entertainment and social spectacle, often layered with humor, as seen in Jan Massys’s painting depicting a wordplay puzzle mocking foolishness.

However, viral imagery could also spread misinformation. False narratives about Indigenous peoples, such as those portraying Caribbeans as cannibals, justified colonial expansion. Artworks like Jan van der Straet’s engraving of Amerigo Vespucci encountering cannibals highlight how images manipulated perceptions, a cautionary tale for both historical and modern contexts.

Today, we recognize how images shape self-image, virtue signaling, and the spread of harmful ideas online. This was uncharted territory during the Renaissance, as paintings provided the public with a new visual vocabulary to navigate a rapidly changing world. The proliferation of images contributed to a complex landscape of knowledge, reminiscent of the constant influx of information we experience today.

Art historian Porras draws parallels between Renaissance artworks and contemporary viral images, noting how memes and formats are adapted beyond their original contexts. As an illustration, she compares historical scenes of debauchery to the “jealous girlfriend” meme, demonstrating how far the art of the Renaissance has influenced our understanding of virality and image manipulation.