Drought Forces Kenya’s Maasai and Other Cattle Herders to Consider Fish and Camels

For generations, the Maasai of Kenya have relied on cattle for their livelihood, deriving blood, milk, and meat from their herds. Cattle have been integral to their diet and culture, symbolizing wealth and playing a central role in social rituals and ceremonies. However, the ongoing drought in Kenya has severely impacted livestock populations, pushing the Maasai and other pastoralist communities to explore new forms of sustenance and livelihood.

The recent years-long drought has resulted in the deaths of millions of livestock across East Africa, forcing traditional cattle herders to adapt to new food sources. For the Maasai, who traditionally viewed fish as foreign and inedible—due to its resemblance to snakes and its unfamiliar smell—this shift represents a significant cultural change. Maasai Council of Elders chair Kelena ole Nchoi reflects on this shift, noting that fish was never part of their diet due to their historical lack of exposure to lakes and oceans.

The drought has left vast stretches of land barren and unable to support cattle, leading to widespread loss. According to the Kenya National Drought Management Authority, 2.6 million livestock perished in early 2023, causing an estimated economic loss of 226 billion Kenyan shillings (approximately $1.75 billion). The situation has been compounded by increased urbanization and shrinking grazing land, compelling pastoralists to seek alternative sources of income and sustenance.

In response, the local government in Kajiado County, near Nairobi, has launched fish farming projects to support pastoralists. These initiatives aim to diversify income sources and mitigate the impacts of climate change. Charity Oltinki, a Maasai woman who lost nearly 100 cows to the drought, has embraced fish farming. With support from the county government—providing pond liners, tilapia fingerlings, and feed—Oltinki has successfully harvested and sold fish, with the largest fetching up to 300 Kenyan shillings (about $2.30) each.

Similarly, Philipa Leiyan, another Maasai from Kajiado, has taken up fish farming alongside traditional livestock keeping. The county’s fish farming program, which began in 2014, now supports approximately 600 pastoralists. The initiative, which faced initial skepticism, has grown significantly since the drought began in 2022. Benson Siangot, Kajiado’s fisheries director, notes that the program helps address food insecurity and malnutrition while providing economic relief.

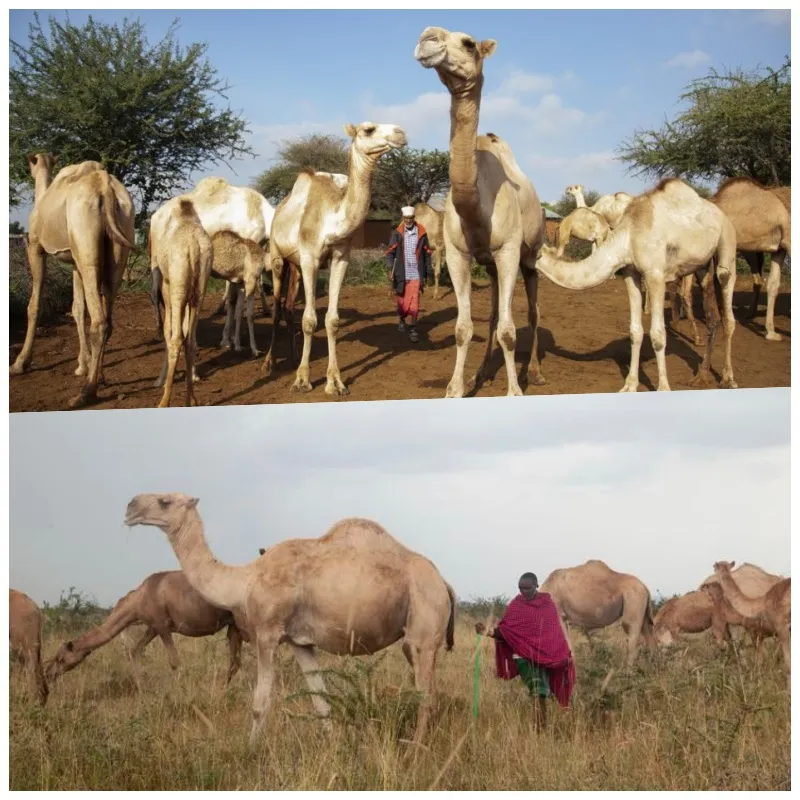

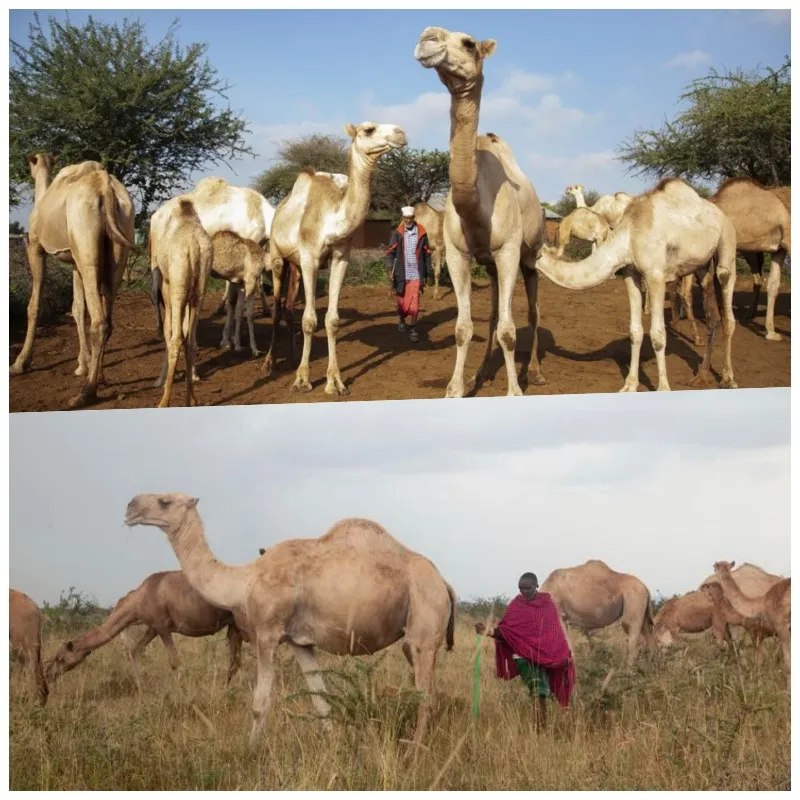

Beyond fish, other pastoralist communities in Kenya are also adapting to the changing climate. The Samburu, a group with cultural similarities to the Maasai, have turned to camels as a more drought-resistant alternative to cattle. Abdulahi Mohamud of Lekiji village, who lost 30 cattle during the drought, now manages 20 camels. He finds camels more suitable for arid conditions due to their ability to graze on shrubs and endure harsh environments.

Camels are more expensive than cattle, with prices ranging from 80,000 to 100,000 Kenyan shillings ($600 to $770), compared to cows priced between 20,000 and 40,000 shillings ($154 to $300). Despite the higher cost, Mohamud sees the investment as worthwhile due to the camel’s resilience. Similarly, Musalia Piti, a 26-year-old Samburu, has shifted his family’s focus to camels after losing 50 cattle. Camels provide a reliable source of income and can be sold for traditional ceremonies, such as weddings, where cattle are traditionally given as dowries.

Samburu elder Lesian Ole Sempere underscores the importance of maintaining cattle for cultural practices, even as herds become smaller. The adaptation to camels and fish highlights the broader trend among pastoralists in Kenya and East Africa to find sustainable solutions amid the challenges posed by climate change and environmental degradation.