Discover why higher intelligence comes with a cost in “The Price of Intelligence.”

A recent study published in Science has uncovered a surprising truth about the human brain: our most evolved and sophisticated brain regions are also the ones that age the fastest. This revelation raises intriguing questions about the relationship between intelligence and brain aging.

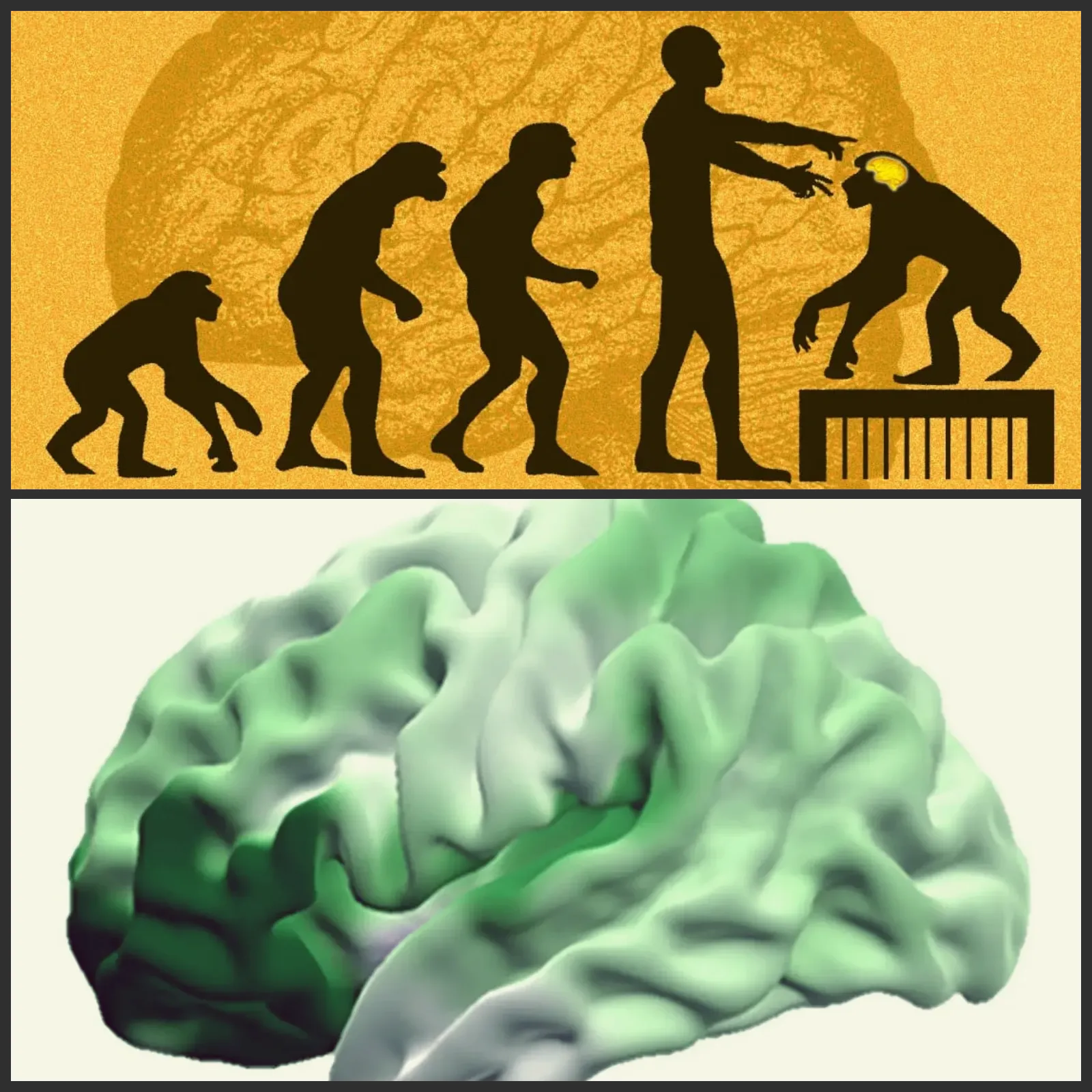

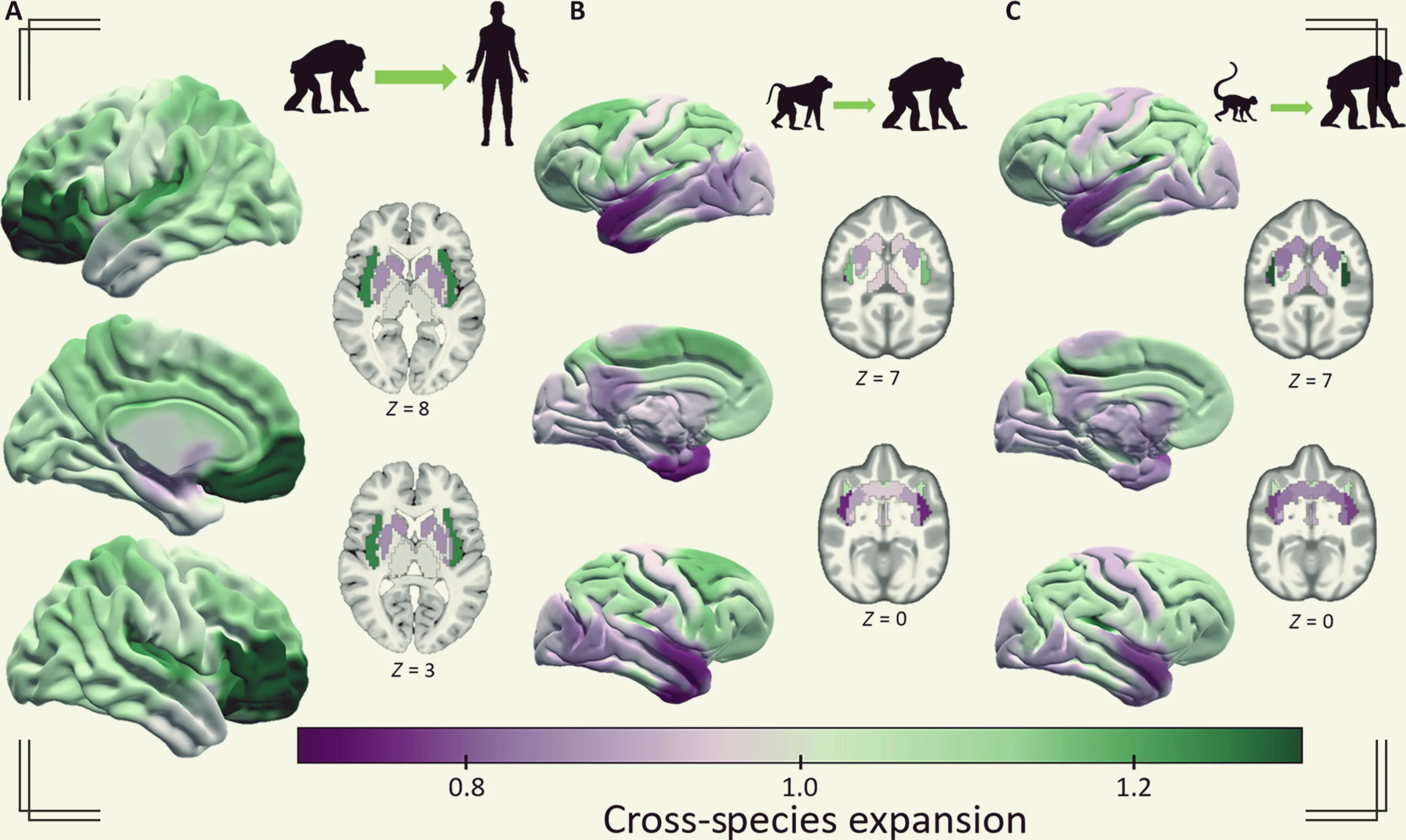

Throughout evolution, the human brain has grown in size and complexity, enabling advanced language use, communication, and complex cognitive functions. How the brain has evolved and why it evolves in certain ways continues to fascinate neuroscientists. One approach to understanding this evolution is to compare our brains with those of our closest relatives, such as chimpanzees. Although chimpanzees are not direct ancestors of humans, they share a common ancestor with us from around 6 to 8 million years ago and exhibit many similar genetic and anatomical features.

Researchers at the Jülich Research Institute in Germany developed an imaging analysis tool to compare the brains of 189 chimpanzees and 480 human volunteers. They found that the human brain contains about 86 billion neurons—three times the number found in a chimpanzee’s brain, which has about 28 billion neurons. Both species have 17 distinct brain regions, with some of these regions being roughly the same size. However, certain areas, such as the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), are significantly larger in humans. The OFC plays a crucial role in cognition and decision-making, and its enhanced development in humans highlights our advanced cognitive abilities compared to other primates.

The researchers also examined how these brain regions change with age. It is well-known that after the age of 30, the human brain gradually loses volume, neurons lose their connections, and aging accelerates. Conditions like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases further exacerbate this process. This pattern is also observed in other primates, but the study aimed to identify whether there are differences in how human and primate brains age.

The study included volunteers aged 20 to 58 and chimpanzees aged 9 to 50. Results showed that brain function declines across all regions with age, but some areas, particularly the prefrontal cortex and OFC, deteriorate much faster in humans compared to chimpanzees. These regions, crucial for thinking and cognition, experience accelerated aging relative to other primate species. Ironically, the very traits that have evolved to give humans a cognitive edge are also the ones that age the most rapidly.

This research marks a significant advance in our understanding of brain aging. However, the exact reasons why these advanced brain regions age more quickly remain unclear. One hypothesis suggests that these areas are under more stress as they handle complex tasks, leading to faster neuron loss over time.

As we continue to explore these findings, it becomes evident that the pursuit of higher intelligence may come at the cost of faster brain aging.