Myanmar’s Desperate Turn to Social Media to Sell Kidneys Amid Rising Poverty

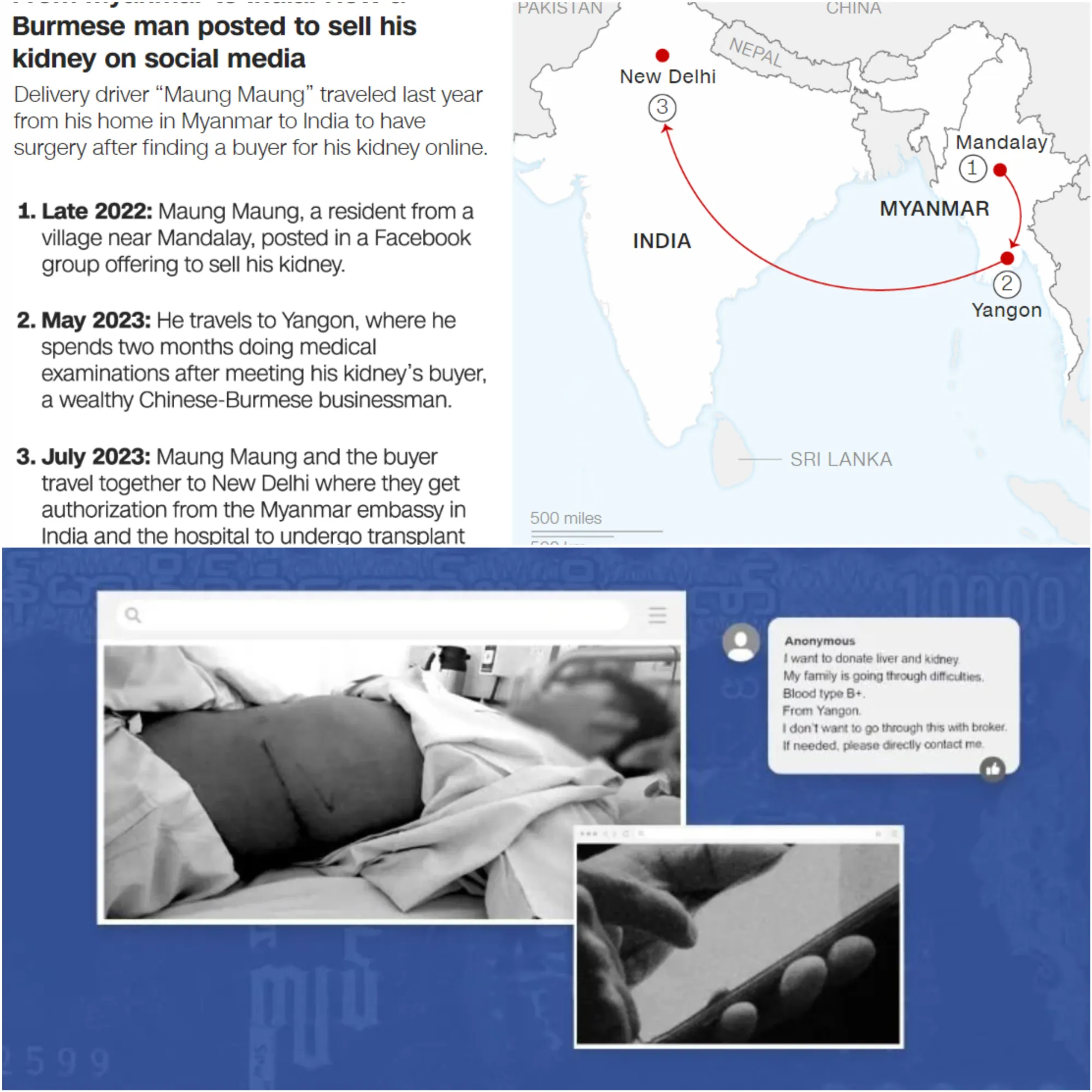

In Myanmar, a country torn apart by civil war and economic collapse, desperation is driving some of the poorest citizens to extreme measures—selling their kidneys via social media platforms like Facebook. Maung Maung, a delivery driver from Mandalay, is one such individual whose story highlights the grim reality faced by many. After being detained and tortured by Myanmar’s military junta, he was released to find his family drowning in debt. In a moment of despair, he turned to Facebook, offering to sell his kidney to feed his family.

In July 2023, Maung Maung traveled to India where he underwent transplant surgery, selling his kidney for 10 million Burmese kyat ($3,079)—almost double the average annual income in Myanmar. His story is far from unique. A year-long investigation uncovered a growing trend of desperate individuals in Myanmar turning to the illegal organ trade, facilitated by agents who arrange surgeries in countries like India, where selling organs is illegal but enforcement is lax.

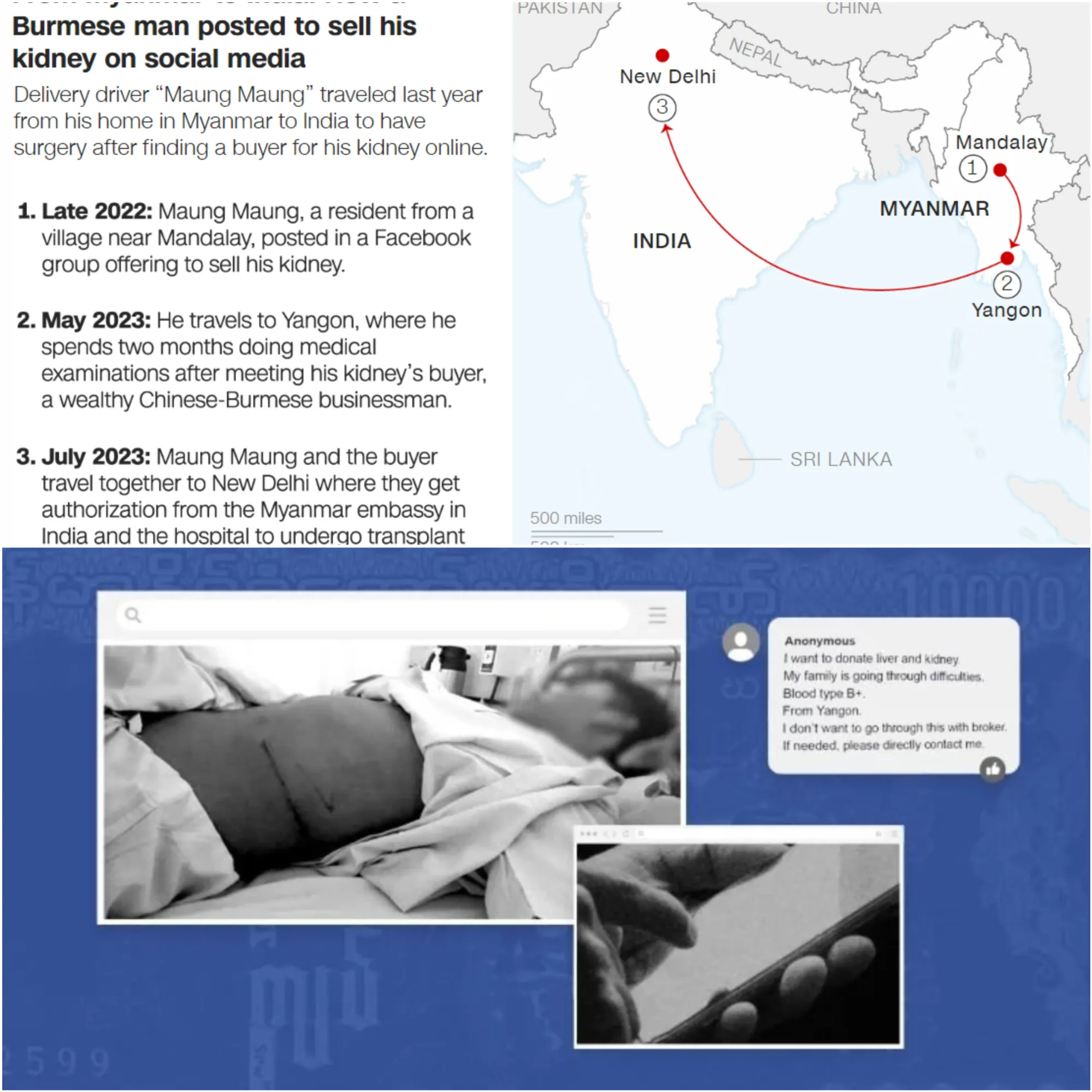

The illegal kidney trade is flourishing on social media, with Burmese-language Facebook groups being used as platforms where sellers and buyers connect. Meta, Facebook’s parent company, has acknowledged removing some of these groups, but the problem persists. Facebook’s rules prohibit the trade of human body parts, yet posts offering kidneys continue to appear, driven by the dire circumstances in Myanmar.

Since the military coup in 2021, nearly half of Myanmar’s 54 million people have fallen below the poverty line. Foreign investment has plummeted, unemployment is rampant, and the cost of basic goods has skyrocketed. For those like Maung Maung, selling a kidney seems like the only option to escape crushing poverty.

April, a 26-year-old former garment worker, also made the heartbreaking decision to sell her kidney. After abandoning her dream of becoming a nurse, she turned to Facebook in a desperate bid to save her cancer-stricken aunt. Her story mirrors that of many others, who see no alternative but to sell a part of themselves to survive.

The illegal organ trade operates through a network of agents who forge documents to facilitate transplants in India. Despite strict laws, these agents manipulate the system, presenting donors as relatives of recipients to bypass legal hurdles. Myanmar’s embassy in India and local authorization committees often turn a blind eye, overwhelmed by the volume of cases and the complexities of verifying documents from another country.

The consequences for sellers are severe. While a person can live with one kidney, the risks are significant, and the psychological toll can be devastating. Maung Maung, now back in Mandalay, is in constant pain, and the money he earned is quickly dwindling. Yet, despite the hardship, he does not regret his decision, as it was his only means to keep his family alive.

The illegal kidney trade in Myanmar is a stark reminder of the human cost of poverty and conflict. As the situation in the country deteriorates, more individuals may be forced to make similar sacrifices, perpetuating a cycle of desperation and exploitation.