Life at the Ends of the Earth: Ittoqqortoormiit

Located in the far northern reaches of Greenland, Ittoqqortoormiit is known as the “most remote place in the world.” Situated 800 kilometers from the nearest town and covered in ice year-round, this small village is a prime destination for adventure seekers and photographers hunting the “Arctic ghost.”

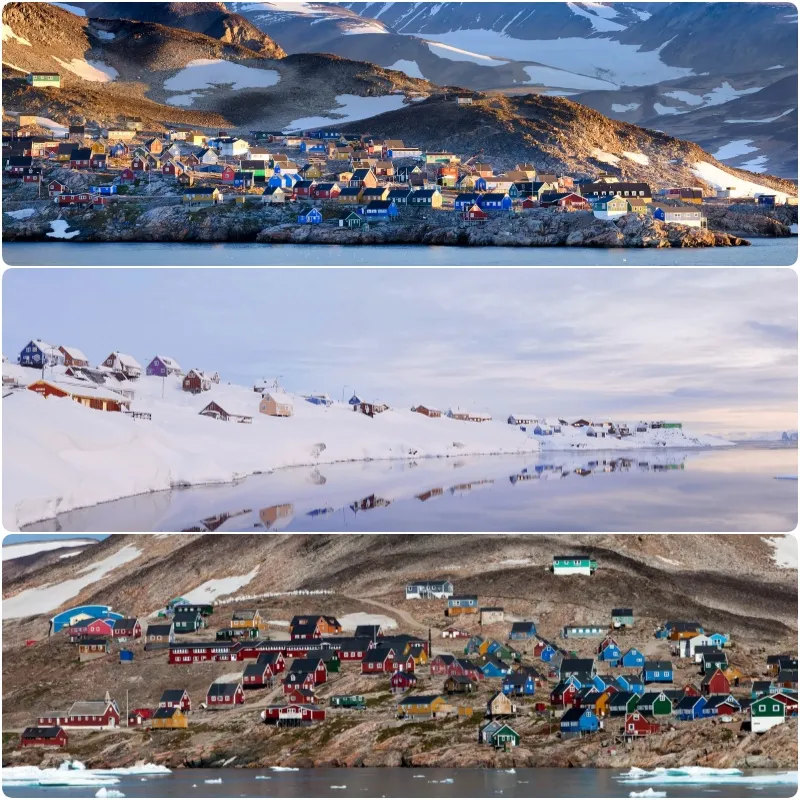

With a population of about 370, Ittoqqortoormiit is characterized by its brightly colored houses nestled between the Northeast Greenland National Park—the largest national park in the world—and Scoresby Sund—the largest fjord system in the world. The local inhabitants primarily engage in hunting, and polar bear hides are often displayed on the scaffolding of many homes. There are no roads leading to the village; visitors can only reach Ittoqqortoormiit by airplane, boat (which operates only in the summer), or snowmobile.

Situated above the Arctic Circle, Ittoqqortoormiit is a remote, frigid land. Visitors can explore the village’s main attractions within about 30 minutes on foot. The village features a church, a police station, a bar, a guesthouse, a heliport, a small supermarket that receives supplies via two ships each season, and a small travel agency. Many are shocked by the exorbitant prices of goods and wonder how locals can afford them on their limited incomes.

The surrounding area is home to polar bears, musk oxen, and millions of seabirds nesting on drifting icebergs. The village is covered in ice and snow for nine months of the year. The residents are primarily Inuit, an indigenous group renowned for their ability to endure extreme cold.

In 2025, Ittoqqortoormiit will celebrate its 100th anniversary. Like many other remote places, the village is facing a declining population as more young people move to larger cities for education and employment. Additionally, climate change is causing ice to freeze later and melt earlier, impacting the culture and lifestyle of the indigenous community.

A group of travelers from Reykjavik, Iceland, landed at Nerlerit Inaat Airport, 40 kilometers from the village. They set up camp in a small tent near the airport on their first night, with temperatures dropping to minus 30 degrees Celsius. After sawing frozen cod on the ice, two local guides melted ice to make water and boiled the fish for a simple dinner. For Hall, one of the travelers, it was an experience of unprecedented cold, and he felt his legs cramping.

In recent years, Ittoqqortoormiit has promoted itself as a destination for explorers, where one can take icebreaker boat trips, hike across the tundra to view drifting ice, and explore a part of the world seen by few. However, when a local police officer waved to Hall’s group as they passed by, he no longer felt like a solitary explorer but rather “a part of this remote community.”